John C. Frémont’s Pathfinder Flag

Published flag histories often include information that has not been produced by careful and thorough research. Various errors originated with histories written many years ago. Writers of more recent books and articles have often accepted far too much from these earlier flag histories without researching the original sources. The flag of John C. Frémont is one flag that has not received the careful research it deserves. Sometimes called the pathfinder flag, this is an interesting and unique flag of American history.

More often than not, illustrations portraying this flag are grossly inaccurate. Details written about the flag’s design are not only often wrong, but they fail to tell the real story which is even more interesting than incorrect information usually related. Finally, most histories assert that Frémont carried his flag on all of his expeditions to the West. This claim is far from certain.

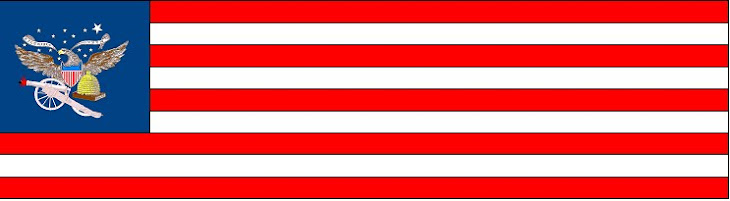

Since Stars and Stripes almost always have blue cantons with white stars, the Frémont flag is usually shown following that pattern. Even when the canton is shown white, the stars are often shown as blue stars on a white background. However, the original flag is in the collection of Los Angeles’ Southwest Museum. It has a white canton with white stars that are outlined in blue.

A flag history written in 1964 states, “At the time a personalized Stars and Stripes was not illegal—merely distasteful.” Another flag history, published in 2002 maintains that, “Because Fremont was on a topographical expedition into areas claimed by Mexico, he chose not to carry a regular U.S. flag.” Actually, Stars and Stripes that included the American eagle amid the stars of the union were not at all uncommon in the nineteenth century. The “Indian Department” which at the time was part of the War Department provided flags to Native Americans that included eagles in their cantons. Lewis and Clark presented similar flags to native tribes during their expedition to the Northwest. Trappers and traders also used trade flags displaying eagles in their unions. The Frémont flag is unique only it its depiction of a peace pipe in place of the usual olive branch. The flag is also unusual in its use of a white canton and blue outlined white stars. However, an eagle was not unusual in the flag of an explorer of the American West.

What then is the actual story of the Frémont flag? While we are not sure of all the details, we do know the a great deal about the history of this famous flag. In 1838 John Charles Frémont received a U.S. Army commission as a second lieutenant in the newly formed Corps of Topographical Engineers. The corps had the charge of mapping unknown territories of the United States. He learned mapping from Joseph Nicollet in an expedition to the upper Mississippi in 1838 to 1839. After marrying Jesse Benton, daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton in 1841, Frémont let his first expedition to the Rocky Mountains. Senator Benton encouraged his son-in-law to apply to the Secretary of War for funds to purchase presents, which would presumably include flags, for presentation to indigenous people. Benton noted, “. . . it is indispensable that the officer who carries the flag of the U. States into these remote regions, should carry presents. All savages expect them; they may even demand them; and feel contempt & resentment if disappointed.” Military requisitions show that Frémont obtained glass beads, fishhooks and flags for his expeditions. Frémont, in a report for one the expeditions, described a meeting with Native Americans. “Having made the customary and expected presents which ratified the covenants of good will and free passage over their country,” he noted “we left the village, escorted by their chiefs.” The ratification of “the covenant of good will” with native tribes usually involved the presentation of a U.S. flag provided by the Indian Department. We can see that Frémont, as an officer of the Topographical Engineers almost certainly carried the U. S. flag on his expeditions.

Frémont‘s Pathfinder flag was made by Jessie Benton Frémont for her husband’s first expedition to the Rocky Mountains. She followed the basic pattern of the flags provided by the Indian Department. The bunting stripes of the flags fields may have come from a purchased U.S. flag with Jessie replacing the usual starry union with a piece of white linen. On the white fabric, she painted twenty six white stars outlined in blue. Between the two undulating rows of stars, she painted an eagle holding arrows in the right talons and a calumet or peace pipe in the left talons. This was this flag that Frémont raised on the highest peak of the Wind River chain of mountain in what is now Wyoming. Understandably, he did not present this flag to any native tribes, but kept is as a prized souvenir. Returning to the East, Frémont presented the memento back to his wife upon the birth of their daughter Elizabeth. Whereupon, Jessie Frémont backed the flag with a piece of lilac silk cut from her wedding gown. She embroidered the words “Rocky Mountains” with the year “1841” on the silk backing. As a final decoration, she also embroidered a butterfly on the silk cloth. There is no record that Frémont ever carried that flag to the West again. However, it is hard to prove the negative. It is possible that he carried the flag on a subsequent trip west, and that the fact was not recorded. Still, one would wonder why other years were then not added to the embroidery to commemorate other expedition where the flag would have been flown. Also, the embroidered silk fabric hardly seems appropriate material to be carried on the arduous trips that the subsequent expeditions certainly were. At any rate, the flag was inherited by Elizabeth Frémont, Jessie and John’s daughter. Early in the twentieth century, she donated the prized artifact to the Southwest Museum, where it remains today. The acquisition record of the Southwest Museum for the flag note the following: “It is unknown if this is the flag Fremont flew in California.” It is likewise unknown if Frémont ever flew this flag in Utah. The record of Frémont’s expedition to Utah records one instance where he met an important Ute leader, Chief Walkara, known to the whites as Chief Walker. Frémont recorded: “He [Walkara] knew of my expedition of 1842; and, as a token of friendship, and proof that we had met, proposed an exchange of presents. We had no great store to choose out of; so he gave me a Mexican blanket, and I gave him a very fine one which I had obtained in Vancouver.” This would have been an excellent time to present a flag as a token of “the covenant of good will.” However, apparently Frémont had already depleted his store of gifts, if he brought any with him on his trip to the Great Basin. Still, as a U.S. Army officer, he would have carried the flag of the United States.

England's flag of St. George is a red cross on a white field. By legend Saint George, England's patron saint, slew a dragon to save a maiden. George carried the white shield of purity and innocence. Dipping his lance into the dragon's blood, he outlined a red cross on his shield. English medieval soldiers wore St. George's cross front and back to identify them in battle. Thus red and white come from England.

England's flag of St. George is a red cross on a white field. By legend Saint George, England's patron saint, slew a dragon to save a maiden. George carried the white shield of purity and innocence. Dipping his lance into the dragon's blood, he outlined a red cross on his shield. English medieval soldiers wore St. George's cross front and back to identify them in battle. Thus red and white come from England.

Frémont‘s Pathfinder flag was made by Jessie Benton Frémont for her husband’s first expedition to the Rocky Mountains. She followed the basic pattern of the flags provided by the Indian Department. The bunting stripes of the flags fields may have come from a purchased U.S. flag with Jessie replacing the usual starry union with a piece of white linen. On the white fabric, she painted twenty six white stars outlined in blue. Between the two undulating rows of stars, she painted an eagle holding arrows in the right talons and a calumet or peace pipe in the left talons. This was this flag that Frémont raised on the highest peak of the Wind River chain of mountain in what is now Wyoming. Understandably, he did not present this flag to any native tribes, but kept is as a prized souvenir. Returning to the East, Frémont presented the memento back to his wife upon the birth of their daughter Elizabeth. Whereupon, Jessie Frémont backed the flag with a piece of lilac silk cut from her wedding gown. She embroidered the words “Rocky Mountains” with the year “1841” on the silk backing. As a final decoration, she also embroidered a butterfly on the silk cloth. There is no record that Frémont ever carried that flag to the West again. However, it is hard to prove the negative. It is possible that he carried the flag on a subsequent trip west, and that the fact was not recorded. Still, one would wonder why other years were then not added to the embroidery to commemorate other expedition where the flag would have been flown. Also, the embroidered silk fabric hardly seems appropriate material to be carried on the arduous trips that the subsequent expeditions certainly were. At any rate, the flag was inherited by Elizabeth Frémont, Jessie and John’s daughter. Early in the twentieth century, she donated the prized artifact to the Southwest Museum, where it remains today. The acquisition record of the Southwest Museum for the flag note the following: “It is unknown if this is the flag Fremont flew in California.” It is likewise unknown if Frémont ever flew this flag in Utah. The record of Frémont’s expedition to Utah records one instance where he met an important Ute leader, Chief Walkara, known to the whites as Chief Walker. Frémont recorded: “He [Walkara] knew of my expedition of 1842; and, as a token of friendship, and proof that we had met, proposed an exchange of presents. We had no great store to choose out of; so he gave me a Mexican blanket, and I gave him a very fine one which I had obtained in Vancouver.” This would have been an excellent time to present a flag as a token of “the covenant of good will.” However, apparently Frémont had already depleted his store of gifts, if he brought any with him on his trip to the Great Basin. Still, as a U.S. Army officer, he would have carried the flag of the United States.

Frémont‘s Pathfinder flag was made by Jessie Benton Frémont for her husband’s first expedition to the Rocky Mountains. She followed the basic pattern of the flags provided by the Indian Department. The bunting stripes of the flags fields may have come from a purchased U.S. flag with Jessie replacing the usual starry union with a piece of white linen. On the white fabric, she painted twenty six white stars outlined in blue. Between the two undulating rows of stars, she painted an eagle holding arrows in the right talons and a calumet or peace pipe in the left talons. This was this flag that Frémont raised on the highest peak of the Wind River chain of mountain in what is now Wyoming. Understandably, he did not present this flag to any native tribes, but kept is as a prized souvenir. Returning to the East, Frémont presented the memento back to his wife upon the birth of their daughter Elizabeth. Whereupon, Jessie Frémont backed the flag with a piece of lilac silk cut from her wedding gown. She embroidered the words “Rocky Mountains” with the year “1841” on the silk backing. As a final decoration, she also embroidered a butterfly on the silk cloth. There is no record that Frémont ever carried that flag to the West again. However, it is hard to prove the negative. It is possible that he carried the flag on a subsequent trip west, and that the fact was not recorded. Still, one would wonder why other years were then not added to the embroidery to commemorate other expedition where the flag would have been flown. Also, the embroidered silk fabric hardly seems appropriate material to be carried on the arduous trips that the subsequent expeditions certainly were. At any rate, the flag was inherited by Elizabeth Frémont, Jessie and John’s daughter. Early in the twentieth century, she donated the prized artifact to the Southwest Museum, where it remains today. The acquisition record of the Southwest Museum for the flag note the following: “It is unknown if this is the flag Fremont flew in California.” It is likewise unknown if Frémont ever flew this flag in Utah. The record of Frémont’s expedition to Utah records one instance where he met an important Ute leader, Chief Walkara, known to the whites as Chief Walker. Frémont recorded: “He [Walkara] knew of my expedition of 1842; and, as a token of friendship, and proof that we had met, proposed an exchange of presents. We had no great store to choose out of; so he gave me a Mexican blanket, and I gave him a very fine one which I had obtained in Vancouver.” This would have been an excellent time to present a flag as a token of “the covenant of good will.” However, apparently Frémont had already depleted his store of gifts, if he brought any with him on his trip to the Great Basin. Still, as a U.S. Army officer, he would have carried the flag of the United States.