U.S. Flag in the Twentieth Century

The Twentieth Century saw the number of U.S. States increase from forty-five to fifty. Five flags mirrored that growth. An increase from forty-five to forty-six in 1908 for Oklahoma; a jump from forty-six to forty-eight for New Mexico & Arizona in 1912; Alaska made forty-nine in 1959; and finally, in 1960, Hawaii brought the total to fifty. There it has remained for fifty years. Only the forty-eight star flag, with 47 years, approaches the longevity of the fifty star flag.

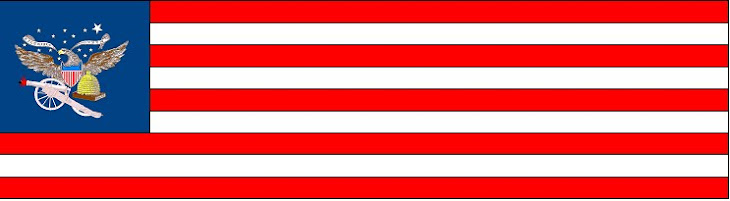

The common pattern of stars and stripes has existed since the American Revolution. But the admission of new states has hardly been smooth or predictable. For most of the flag's history, the pattern of stars has been anything but "regulation." Sometimes the Army and the Navy had different versions of the flag. During the Civil War, the white stars even turned gold on Army National Colors. Silver paint oxidized and turned the stars black. For that reason gold paint, which does not oxidize, was substituted. Cavalry standards of the era even cut a "v" from the stripes to form a swallow tale flag. American flags were anything but uniform.

The regularity we take for granted did not come into being until 1912. President William Howard Taft appointed a blue ribbon, or perhaps better described, a red, white and blue committee. Spanish American War hero, Admiral George Dewey, served as chairman. Very much like a military formation, the stars were arranged in six even rows of eight stars each. Looking at that pattern of stars, one can almost hear the military order, "Dress and Cover!" For those who have not enjoyed the privilege of standing a military formation. The stars in the forty-eight star flag lined up evenly horizontally and vertically, not in staggered rows as we have known before and since. Nevertheless, the real innovation of 1912 came with the establishment of ratios for all the elements of the United States flag: the ratio of length to width, the ratio of the dimension of the blue union to the whole. Even the stars were assigned a ration of 0.0616 of the hoist. Why 0.0616 and not 0.0615? I envisioned President Taft sitting up in the Lincoln bed with a yellow legal pad and a slide rule working it out. Actually, 0.0616 is the decimal version of the relation of the diameter of the stars to the width of the stripes. A stripe is ⅟13th of the width of the flag or 0.0769 which rounds off to 0.077. The stars are ⅘th or 0.8 of the width of the stripes. The decimal number 0.077 time 0.8 equals 0.0616. I don't know who figured that one out; probably not President Taft. Nevertheless, it was President Taft who made it all official. He made the forty-eight star flag official by Presidential Proclamation. That is the pattern that has been followed by succeeding presidents when new stars have been added to the flag.

Are the stars actually that exact ratio? Well, not exactly. The stars on U.S. flags used to be appliquéd on the blue field. Considering the number of stars front and back, that becomes a tedious and expensive process. Fifty stars on the front and fifty stars on the back for one hundred stars on each flag. Flag makers have learned tricks to make producing starry unions easier. Nonetheless only stars on large flags are appliquéd in place today. Most flag have printed or embroidered stars. The beautiful embroidered stars look elaborate. Many people assume they are costly to make. Yet they are actually embroidered by sophisticated machines that produce starry field rapidly. While the machines are expensive, once purchased they produce large numbers of star spangled unions that are much more cost effective that appliquéd ones would be. Still, they can only produce stars of a few standard sizes. Flag makers get as close to the 0.0616 as possible. Even President Taft and Admiral Dewey would agree that these flags are beautiful.

Figuring the dimensions of the United States flag using the proportions scaled using the ratios based on the hoist or with is nonetheless awkward. Basing the ratio on the width of the stripe actually makes the task of constructing the flag easier. It is logical that if the width of the stripe is defined as one, the width of the flag is thence thirteen. Converting the rest of the ratios established in 1912, we find that the length of the flag is 24.7 which rounds to 25 units equal to the width of the stripe. The diameter of the star is no longer the complex 0.0616 ordained in 1912; it is now simply four fifths or eight tenths of the width of the stripes. See the diagram shown below to find the ration of the flag's elements in ratio to the width of the stripes. Flags of different sizes can be easily drawn, painted or sewn.

How do we make a five pointed star? Heavens to Betsy. The story of Samuel Wetherill, his safe and Betsy Ross' star is one that is seldom told. Well, that's another story for another time.

No comments:

Post a Comment