When the National Flag Conference of 1924 established the rules of flag display, the believed that they were following the rules of heraldry in determining how the flag should be displayed. The upper left of the shield is called the dexter chief, and is the most honorable quarter of the shield. A square portion of the dexter chief is called the canton. In heraldry cantons are often awarded by the monarch as augmentations of honor to commemorate some notable achievement. The committee, therefore, decided that the union of stars would always be displayed in the dexter chief or canton corner of the flag. That is why the union of stars is often called the canton. That is also why the blue starry field is always displayed in the upper left-hand corner when the U.S. flag is hung flat on the wall.

However, the committee allowed one exception to this rule. When the flag is draped on the casket the blue field is placed over the left shoulder of the deceased person. If the rules placing the union in the "canton" corner were applied, the blue field with stars would be placed over the right shoulder.

To explain such inconsistencies, romantic stories often emerge. Two such romantic stories to explain flag draped coffins appeared. First, and most often related, is the explanation given by Colonel James Moss, a respected flag historian: "For generations the customary way of indicating death, the opposite of life, has been to reverse objects." The second story, also described by Moss, "Another explanation—a romantic one—is that the soldier having devoted his life to his Country, the Flag of his country embraces him in death, necessitating the flag facing the soldier which places the blue field to the Flag's right, which is the same as the right of the observer who faces the casket." The second story is harder to understand. Basically, if the flag—as does a person—has a left and right, it has a front side and back side. It the flag is flipped over reversing the position of the canton, then the flag is facing down and symbolically embracing the fallen soldier. Nice stories, but likely an incorrect explanations.

There is another understanding of heraldic rules that was dismissed by the committee. This view is actually the better one. The rules of heraldry were promulgated to facilitate the designing and display of shields and crests. Some rules can be and are applied to the display of flags. Other rules of heraldry do not neatly apply to the design or display of flags. A vexillologist (a student of flag study) could argue that flags should not be viewed as a subsection of heraldry. Heraldry and its rules do not control vexillology.

To begin with, a flag is not a shield. A flag has two sides, a front or obverse and a back or reverse. A shield has a front, but the reverse side carries no design. The back of a shield simply has the straps by which the shield is held and wielded. So, when a shield is displayed, it is never flipped over to show its back.

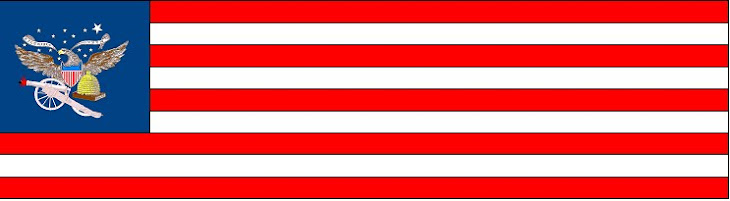

The U.S. flag has a front and back. Many believe that the front and back of the American flag are the same. Nonetheless they are actually different. The back of the flag is the mirror image of the front. When the flag is displayed on a wall with the stripes running horizontally, we see the front or obverse. When the stripes run vertically, we see the back or reverse of the flag.

If we stretch the design of the United States flag over a shield (see above) with the stripes running horizontally, the stripes in heraldry are called bars. If we stretch the flag over a shield so that the stripes run vertically, the stripes are then called pallets in heraldic terms. The resulting shields are not identical, but are two similar yet distinct designs. If either shield is rotated to cause the stripes to run another direction, the canton moves from the observer's left (dexter) side to the observer's right (sinister) side.

Had this interpretation of heraldry been adopted, we would simplify things by always displaying the front or obverse of the United States flag. Whenever the flag is rotated to change the direction of the stripes from horizontal to vertical, the union would move from the observer's left to the observer's right. This would have the added advantage that when flags include lettering, such as the with the Utah State flag, they could be displayed uniformly with the U.S. flag without words and designs appearing backwards.

This explains the origin of placing the stars over the deceased left shoulder when the flag is draped on a casket. It is simply done to show the front of the flag. Many draped flags have been banners bearing royal arms or other coats of arms. If the design were flipped to place the dexter chief over the right shoulder of the deceased, the reverse of the flag would be displayed. The design would be backwards. The place where a person stands to view the casket determines how the flag appears. The most important thing is to show the front of the flag.

At the right is a picture of the coffin of Denmark's King Frederick IX. The front the flag is displayed. The same pattern in followed in the United Kingdom. The United States military no doubt followed the European pattern for draping military caskets with flags.

Heraldry and the flag's own right? There is more than one way to look at it. The National Flag Convention of 1924 might not have picked the best interpretation.

America’s Founders Wrote It Down

5 years ago

No comments:

Post a Comment