Famed as the first ship to carry the Stars and Stripes around the globe, the Sailing Ship Columbia Rediviva is commonly known as the Columbia. Indeed in 1773, this merchant ship was christened simply as the Columbia. This designation was and is a poetic nickname for the United States and honors Christopher Columbus. Columbia was rebuilt in 1787 and given the added Latin name Redivivia meaning revived. The ship's full formal name thus translates from Latin roughly as "land of Columbus reborn." There is something symbolic in her full name. The Boston Tea Party took place the same year the Columbia was first launched. The struggle for independence was then beginning. The Revolution ended in 1784 by the Treaty of Paris, and thirteen British colonies had a rebirth as an independent nation. Three years later, Colombia Rediviva departed from Boston carrying the flag of the newly independent United States of America, indeed she lived up to her name Columbia reborn.

The voyage began on September 30th of 1787. From her rigging, Columbia Rediviva flew a flag displaying thirteen stripes and thirteen stars. Her voyage took her around South America to the Pacific coast of the continent where she discovered, named and explored the lower reaches of the Columbia River. Continuing westward across the Pacific, she made her way around the Asian land mass and Africa back to the Atlantic Ocean. Finally returning to Boston in 1790, she had circumnavigated the globe displaying the Stars and Stripes to the world.

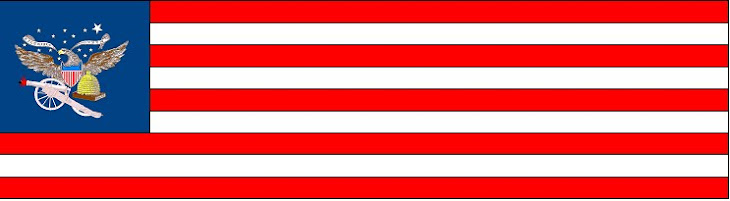

What did the U. S. flag look like that was first carried around the world? We don't know exactly. There were many versions of the first Stars and Stripes. The pattern of stars existed in many variations. The stars usually had five points. Nonetheless, stars on flags sometimes boasted six or more points. Even the stripes showed variety. The flag was most often a red field with six white stripes. In this arrangement the top and bottom stripes are red. Still, a white field with six red stripes was not unknown. Then, the top and bottom stripes were white. On occasion, the stripes were even red, white and blue.

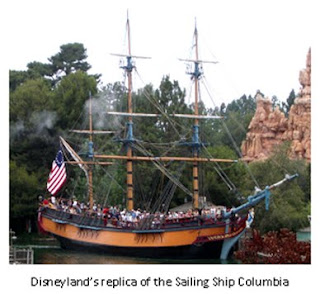

A replica of Columbia Rediviva plies the waters of Disneyland's Rivers of America. She flies the version of the thirteen star flag that is best known, today. Usually called the Betsy Ross flag, this flag displays thirteen five-pointed stars in a circle. Common for most of our nation's later history, this version was uncommon during the revolution. Some flag historians have even asserted the ring of thirteen stars was not contemporary to the American Revolution. However, it appears to have been used. Also used occasionally, was a circle of twelve stars with the thirteenth star at the center. More common is a pattern of stars in rows of three, two, three, two and three. Less common but also used, the stars appeared in rows of four, five and four. Any one of these star patterns could have been shown on the flag carried around the world by Columbia Rediviva. Nevertheless, the voyage lasted more than a year and more than one flag was likely used.

Columbia continued under sail until salvaged in 1806. Yet, she still served as inspiration for the nation. Three U.S. Navy vessels have been named for the Sailing Ship Columbia. Disneyland in 1956 launched a replica of Columbia to honor the vessel. In 1969, the Apollo 11 command module for the first lunar landing bore the name Columbia. The space shuttle Columbia became the world's first reusable space craft flying space missions beginning in 1981. Tragically, she and her seven astronaut crew perished on reentry in 2003. Only Disneyland's Columbia continues in service having sailed the waters of Frontierland for over fifty-four years.

In 1843, Columbia Gem of the Ocean appeared as a patriotic song that still inspires Americans. The song missed being selected in 1931 as our national anthem. It was beat out by another song with a flag connection, the Star Spangled Banner. In the song Columbia the Gem of the Ocean, its name serves as a metaphor for the nation or ship of state. Still, the song concludes with words that must echo shouts that greeted Columbia Rediviva on her return from circumnavigating the globe, "Three cheers for the red, white, and blue."