A United States Air Force Honor Guard conducts a flag-folding ceremony at Ramstein Air Base, Germany.

We Americans often believe that the traditions we observe in displaying our flag are centuries old and universal. In fact, some rules of flag display only had their origin in the Twentieth Century. Some flag traditions may spring from our history as a nation. Other details of our flag usage have origins obscured by the mist of time. Yet through it all the traditions of flag display continue to grow. Franklin K. Lane, the Interior Secretary expressed it well when he said, speaking for the flag, "I am what you make me; nothing more."

One tradition has grown dramatically in recent times, folding the United States flag. The latest embellishment on the folding ceremony counts the number of folds and gives each fold a symbolic meaning. This adds symbolism to a ceremony that has long been impressive. The United States military makes the folding of burial flags a touching part of funerals. Youth organizations have long taught their members to fold the U.S. flag into a triangle forming a cocked hat shape. Nevertheless, we may wonder where this tradition began.

First of all, folding a flag in a triangular pattern is not a universal flag custom. Other nations have no ceremonial fold for flags. Flags are simply folded in a practical way for storage. Actually, when folding any textiles, the simpler the fold the better. Each fold adds stress to the fibers of the material. For new flags currently in use, the number of folds is not that significant. Conversely, for antique flags the number of folds and their complexity can damage fragile fibers hastening the fabric's deterioration. Museums avoid folding flags for storage whenever they can. Flags, rather, are rolled on acid free cardboard tubes backed with acid free tissue paper and covered with cloth or nonreactive polyethylene plastic.

In fact folding the flag into the triangle is not required by the United States Flag Code. The flag may be folded in any appropriate way. The important thing is to care for and store the United States flag in ways that protect it from becoming damaged or soiled. Folding the flag into a triangle is impressive, but it is not required.

Folding the United States flag in its accustomed triangular fold serves much the same purpose as brailing a flag. The triangular fold produces a neat envelope or packet where the flag is wrapped in itself. When the last flap is folded into the pocket produced by folding, the flag is neat and orderly. It is ready to be "stowed" or stored away until its next use.

How did Americans start folding into a triangle? It is often explained that the triangle symbolizes a three cornered cocked hat as worn during the American Revolution. This is likely a romantic explanation created later. The origin is somewhat obscured by the passage of time. However the custom began, early Americans did not record how they folded the flag and why.

There is one narrative that ties to the story of the historical American flag known as Old Glory. Several versions of the story give slightly different details. However, the substance of the story remains the same.

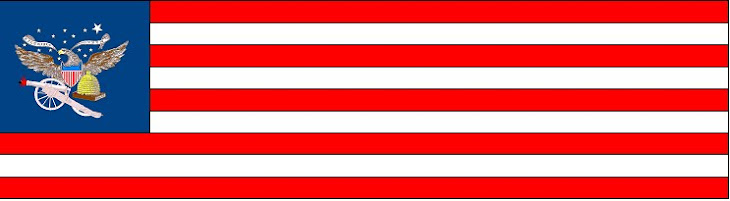

In 1824 a New England ship's captain prepared to embark on a sea voyage. Several ladies of Salem, his home port, made a ship's ensign for the new captain. His mother was part of the group that presented the flag to William Driver. To consecrate the flag, it was folded into a triangle which represented the Christian Trinity. Narrations explained that his was an "ancient custom of the sea." A minister or priest is said to have blessed the flag in the names of the Trinity intoning each blessing while emphasizing corners of the folded flag. As the clergyman said the words "In the name of the Father," the onlookers responded by chanting the word "glory." The word glory was repeated as the names of the Son and the Holy Ghost were added to the blessing. Then Captain Driver hoisted his new ship's flag and informed the crew "I'll call her old glory, boys, old glory."

Having retired from the sea, Driver moved to Nashville, Tennessee. During the Civil War, he hid the flag from Confederates intent on confiscating and destroying it. When Federal troops captured Nashville, Driver met soldiers from the Ohio 6th Infantry and raised Old Glory over the Tennessee State Capitol. The 6th Ohio adopted the motto "Old Glory" as its own. Apparently, Driver gave the regiment a smaller U.S. flag. Did he fold the gift flag in a triangle that was copied by the soldiers for folding other U.S. flags? That is possible, though certainly not documented.

United States Military Regulations of the Nineteenth Century do not mention folding the flag. Even current regulations mention it mainly as a part of funeral ceremonies. How to fold the United States flag is more important to us today than it was in the past.

Narrations have been written giving symbolic interpretation for each fold that is made when folding the United States flag. These can add new meaning to the ceremony as the flag is folded. This will not be the last change to our flag customs. They continue to evolve to reflect the ideals that we find important. They give new meaning to our flag. The Flag of the United States of America is what we make it. It has the meaning we give it. The flag and its meaning will grow as does our nation.